Better Arguing about COVID–19

Don't catapult facts at people, share personal experiences.

There are many terrible things about COVID; one mildly annoying thing is having to talk about it with others. Small talk about masks and local restrictions are about as stimulating as talking about the weather. But as trying as small talk can be, it is worse when someone—especially loved ones—confidently states something about COVID that seems wrong or downright harmful. These disagreements move quickly from debates about basic facts to moral condemnation, with powerful consequences for relationships. According to a recent YouGov survey, 1 in 5 Americans say they have lost at least 1 friend due to disagreements over pandemic related behaviors. And more recently, over an even shorter time horizon, 1 in 7 Americans have lost a friendship over differing vaccination statuses.

What’s driving this disagreement? How can we disagree on basic questions of reality? And why are we so hostile to each other?

There are a few things going on. When we zoom out, Americans have strikingly different ways of navigating the information landscape. Half of Americans are generally untrusting of information sources and show little interest in learning how to better evaluate media. It is easy to attribute this cynicism and apathy to malice, but people live busy lives or simply have lower levels of smartphone adoption and broadband connection. The other half of Americans have approaches to information sources ranging from “Cautious and Curious” to “Confident.” These discrepancies often track alongside educational and generational lines.

Of course, we all know there is an elephant (and donkey) in the room. In today’s partisan media landscape, people of different partisan persuasions often feel like they’re the ones with prescription glasses while everyone else is walking around with 20/1000 vision. This is largely because these two groups seek out different media, hang out in different circles, and actually see and remember things differently. These disparities create an America in which citizens live in somewhat distinct epistemic universes, where the war for truth rages on. Everyone has their own facts, and when these facts cluster amongst teams in a competitive system like democracy, hostility is likely imminent.

COVID is a powerful example of partisans having separate informational worlds—liberals and conservatives have vastly different perceptions of the deadliness of COVID, the efficacy of masks, and the importance of vaccination.

How can we bridge these separate worlds? One idea is using charts and graphs from medical professionals to illustrate the truth about COVID—but these usually serve as kindling for divisive arguments. Instead of facts and statistics, personal experiences may be the route to moral understanding. For example, Carol Williams, a nurse in Aurora, CO, created a viral Facebook post describing her experiences treating COVID patients. "Imagine being the nurse or doctor holding that same patient’s hand and stroking their head weeks later while their ventilator is removed because they haven’t improved and their family then says goodbyes and “I love you’s” over FaceTime while they take their last breath," she wrote.

Recent research from the Center for the Science of Moral Understanding tested the power of personal experiences (versus facts) to bridge divides. In these studies, participants encountered someone who had an opposing political view, and this person grounded their political beliefs in either personal experience or facts. For example, a conservative anti-gun-control person might hear from someone who supports gun control “I believe this because my mom was hospitalized after being hit by a stray bullet, so my personal experience has really made me feel strongly about this.” (experience) or “I believe this because I have read many books and governmental reports on gun policy, so my factual knowledge has really made me feel strongly about this.” (facts) No matter the issue (gun control, taxes, abortion, immigration, and the environment) or the setting (reading about someone online, an in-person one-on-one conversation, the comments of YouTube videos), people were more respectful towards partisans and their views when they used personal experiences to ground their opposing political beliefs.

Not all personal experiences are equally powerful at fostering respect. Our studies show that experiences of harm—enduring personal suffering or witnessing the suffering of loved ones—are the best at bridging divides. People may ignore facts, but they listen when someone is anti-tax because they lost their business, or when someone is pro-environmental restrictions because their kid got sick from drinking tainted water.

The ability of experiences of harm to increase respect likely involves the fact that harm is a universal common currency across morality, and the ability of harm to increase empathy. But our research reveals something else important about grounding beliefs in harm: it makes you seem rational. Charles Darwin recognized long ago that it’s rational for any organism to want to avoid harm, and we all intuitively appreciate the rationality of harm avoidance, even in political opponents. Liberals and conservatives may not see eye-to-eye about taxes and guns, but we can all understand the importance of protecting ourselves and our family from harm.

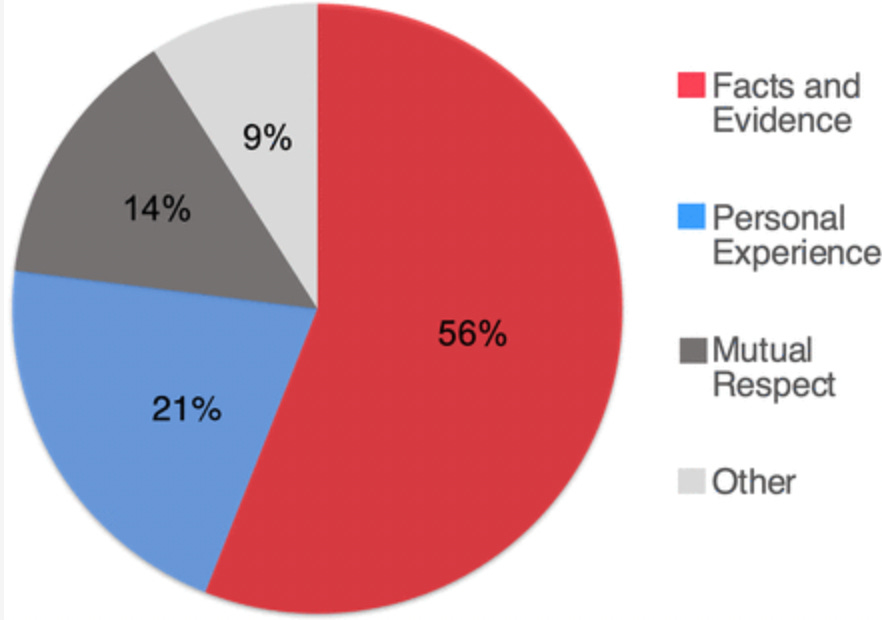

Now that you’ve read this newsletter, it might seem obvious to you that personal experiences of harm bridge moral divides much better than facts. But it isn’t. In a sample of Americans, we find that 56% of participants said they would respect an opposing viewpoint if it was based upon facts and evidence. Only 16% claimed they would respect an opposing opinion if it was based on personal experiences.

The disconnect between what people think bridges divides and what actually bridges divides is one reason why we started this newsletter. We all have intuitions about how to reduce political animosity, but they sometimes lead us deeper into misunderstanding. That’s why we need science to help us evaluate ways to bridge divides. That’s why we need facts.

Despite our work on the power of experiences, facts are important. A functioning society needs truth—a shared set of facts that drive discussions and policy. I am a scientist, as are many of you, and data and statistics help illuminate the path forward on countless issues, including COVID-19. But if you’re having a tense conversation with a neighbor, a cousin, or a parent about masks, social distancing, or vaccines, remember that the surest route to mutual understanding is not through catapulting facts, but instead through sharing personal experiences.

Editing and Research by Will Blakey (@blakey_will)