Does lying about Santa hurt kids?

The ethics (and science) of deceiving children.

I’ve been lying to my kids for their entire lives. Every December, my wife and I tell them that a big Canadian guy is going to break into the house and leave them presents…if they stop fighting with each other, are kind to other kids, and have good manners.

We’re not alone in the deception. Most American parents deceive their kids too, and we all tell ourselves it’s for the magic of the season. Of course, we’re also happy to waive the threat of supernatural punishment over their gullible little heads.

I’m a firm believer in telling my kids the truth, even if it’s hard. When their fish, Max, died, I thought about rushing out to the pet store to replace it before they noticed, but we decided it would be a good opportunity to learn about death. (There were many tears).

But when it comes to Santa, we fight hard to keep the fiction alive. And it’s getting harder. We were watching some grown up movies with the kids (Four Christmases) when Vince Vaughn’s character told his nephews that Santa wasn’t real. Our kids were sitting right on the couch, but luckily, they weren’t fully paying attention. But then, at dinner that night, the question came: “Is Santa…real?”

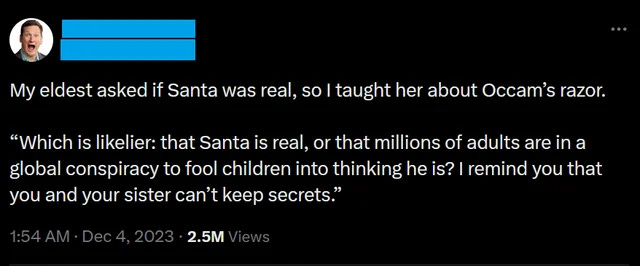

We didn’t want to directly lie, and so we dodged: “Why wouldn’t he be?” “Don’t you get presents on Christmas morning?” Some go a similar route, arguing against the implausibility of a global conspiracy:

(source)

So far, our kids still believe Santa is real. (Except for mall Santas, who are obviously just part of his network). Studies show that most kids believe in Santa and see him as a real being (more so even than mythical creatures like unicorns, or cartoons like Spongebob) until about age 7 or 8, when the illusion starts to fail.

But until that day of lost innocence and magic, it’s worth asking ourselves: Is it wrong to lie about Santa?

Philosophers Ruin Christmas

One philosopher, Immanuel Kant, had a very clear position on lying: Never do it. Kant said that lying is always bad, because the ends can never justify the means. He thought that you couldn’t justify killing one person to save many (like in the classic trolley problem), and that you couldn’t justify a polite lie even if it saved the lives of innocents. To Kant, misdirecting anyone—even a murderer—is immoral.

But most of us are not Kant. In fact, Kant thought that sex was like “sucking a lemon dry,” so he can’t be treated as the final word on joy. Kant didn’t worry about keeping the magic of Christmas alive, and he never had to lie to keep a five-year-old from breaking down in the toy aisle at Target.

The Means to an End: Santa Makes Kids Behave

One way to justify the big lie about the big man is that it makes kids behave. When kids know that someone is always watching, they smarten up. In recent years, Santa’s spying has gotten more personal, with parents hiding an “elf on the shelf” daily that’s meant to watch kids constantly and report their behavior back to Santa.

The same logic of surveillance is why—some psychologists and anthropologists argue—Western society believes in “big Gods,” all powerful deities who watch your behavior and mete out supernatural punishment for sinning. One study shows that believing in Hell is negatively linked to national crime rates, suggesting that the threat of punishment is effective in stopping bad behavior.

Of course, getting coal in your stocking isn’t the same as burning in a lake of fire for all eternity, but not all “Santas” are quite as jolly. In Germany, parents warn their kids about Krampus, a terrifying horned beast (similar to some depictions of Satan) who punishes bad kids by stuffing them in a sack and beating them with birch rods.

Science shows that Santa can make kids behave. One study sampled 440 parents of kids ages 4 to 9 throughout the Christmas period (December 1st to January 31st) and found that Christmas related-activities and reminders (think: decorating the tree or seeing an elf on the shelf)—increases kindness. But directly threatening kids about Santa (“Be nice to your brother or you’re getting coal!”) didn’t make them good.

(Then again, kids may not believe that the threat is credible, since Santa always seems to keep kids on the nice list. The IRB didn’t approve what we’re sure was a planned follow-up study: Krampus stuffing a bad neighborhood kid into a bag and then whooping them.)

And lying can be effective at changing behavior. Helen’s parents told her that the car doesn’t run if the dome light is turned on—which effectively stopped the habit. I tell my kids that failing to brush their teeth will turn them mossy and green, and repeat the old classic “If you keep making that face, your face will freeze like that.”

In Gilmore Girls, Luke cites his so-called secret of parenting to be lying to your kids.

Despite the benefits of teeth brushing and being kind to your sibling, the spirit of Kant lingers like the ghost of Christmas past. Doesn’t it hurt kids to lie to them?

Lying About Santa Isn’t So Bad!

Science shows that lying to Santa doesn’t build long-term resentment. One study interviewed kids and adults to find out when they learned the truth about Santa’s identity and how it made them feel. While a third of the kids and half of the adults felt a bit negative about the hoax, most of their feelings were short-lived, and the majority thought they would continue the tradition with their kids.

People usually vow to stop paying forward traumas—stopping the cycle of injustices done to them by not doing them to their kids. Santa can’t be too bad given that both kids and adults plan to lie to their kids after being lied to themselves.

If anything, believing in Santa might be good for kids’ development. The Santa myth helps kids exercise their fantasy play abilities—a skill that is considered key to cognitive development and developing creative thinking. Most psychologists agree that while outright lying to kids is generally bad, Santa’s existence as a uniquely fantastical entity allows him to transcend the rule.

That being said, lying about Santa can go too far, especially if it’s not developmentally appropriate—creating an elaborate hoax so your teenagers still believe in the jolly elf. One episode of This American Life interviews the Mutchler family, who went above and beyond to make Santa alarmingly real.

When their three kids were little, they planted an old man in the backyard in ratty clothing decorated in bells. When 7-year-old Colin invited him inside, he called himself Kris Kringle and asked to dim the lights to help with his “snow blindness.” These ‘Santa’ variations appeared year after year in their yard, looking for the Mutcher’s and bringing sacks of Rudolph’s bones and an elf who set up a DIY toy workshop in their attic.

The Christmas fiction that the Mutchler’s created was so realistic that their kids believed in Santa up into their teens—leading to arguments between them and their friends. Being convinced about the magic of Christmas up into adolescence was not only uncool, it caused some deep trust issues in their son Adam:

“Adam felt betrayed and was angry about it for years. One year, he came home from college and accused his parents for being the reason he couldn’t trust anyone enough to have a serious girlfriend-- not too different from the sorts of speeches lots of kids make to their parents at that age, except it was about Santa.” (source)

Most families don’t lie as long or as well as Adam’s family, but it’s important to appreciate when a “white lie” turns to something darker.

It’s What in Your Heart that Counts

At the end of the day, what probably makes lying about Santa (or anything else) okay is your intention. Human morality is not just about the deed, but the motivation behind it—it’s why prosecutors have to prove that a defendant had a “guilty mind” when trying to convict them.

Lying to our kids because we love them and want to “keep the magic alive” is almost certainly a good thing, or at least better than lying to them just to make them behave. A flourishing childhood is more about knowing that you are loved than about knowing the literal truth of everything in the world.

There are lots of hard truths in adulthood, so what’s one more year of believing in a jolly man who loves them? And when my kids eventually learn the truth about Santa, I’ll just have to keep them from learning about that philosophical scrooge, Immanuel Kant.

Respectfully disagree, homie.

I was still hanging on through 5th grade! My parents drove me hours to talk to “the real Santa” (as opposed to his many “helpers” in malls) at an elaborate production up in Richmond, VA every year. There may or may not be an entire shelf full of annual pictures of me with this Santa at my parents’ house. #OnlyChild I remain a big fan of the Santa magic. Thanks for this piece and all your other stellar work!