Hidden Brain and Evil Explain

Lessons from death threats

I (Kurt) recently appeared on the podcast Hidden Brain, hosted by Shankar Vedantam, to talk about morality and the growing political divide in America. You can listen to the interview at the link below, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Hidden Brain: Us 2.0: What We Have In Common

Shankar and I discuss questions of politics and our psychology, but there’s a recurring theme: explaining evil. I start with a story about road rage from when I was a teenager. I was driving to a movie with some friends. It was dark, the roads were wet, and I accidentally cut off a man in a Mercedes after almost missing my turn. He leaped out of his car and threatened to kill me. I took off, and then he chased me through a dark strip mall before cornering me. He tried to pull me out of the car, again threatening to kill me, and then slapped me around.

In the podcast, I try to make sense of his aggression and eventually come to see his side of the story, as both another human being and a social psychologist. I understand where he came from: He felt threatened and was lashing out. But is understanding forgiveness? Am I making violence seem okay by explaining why he attacked me?

In the remainder of the podcast, I outline how feelings of threat drive much of our political behavior. When we scream at political opponents, it is not because we want to destroy them but instead because we seek to protect ourselves and the values we care about. There is a lot of science showing that our intuitive perceptions of harm drive our moral judgments. But Shankar noticed a deep ethical tension behind the science of explaining bad behavior.

When we explain why someone does something odious, it can seem like we are condoning their behavior. This tension came up when we discussed the January 6th riots at the Capital, which might seem like an act of evil or a righteous response to evil, depending on how you vote. It also came up when we talked about the actions of the Nazis, although this didn’t make the final cut of the episode.

I don’t condone violence—whether against me or anyone else—but I do believe that we need honest explanations of human behavior. Explaining evil is why social psychology took off in the wake of the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust. Understanding evil is important to preventing it, and studies find that everyday humans do bad things when they are told to, when the situation calls for it, and when it conforms to other people’s behavior.

People are often unsettled by these psychological explanations because—as one paper finds—explaining evil can make it seem more acceptable. People can accuse the “explainers” as guilty of being complicit or of “both-sides-ism.” The German movie “The Downfall” received a lot of pushback because it portrayed Hitler as a fallible human being. And shortly after my Hidden Brain episode was released, I received an email comparing me to a Nazi sympathizer for trying to see the humanity in both sides of the American culture wars.

As we approach a contentious election, there are people on both sides who see betrayal in viewing the “enemy” as human. Still, we (Sam and I) remain convinced that there are better and more hopeful explanations for our political divisions than half the country being evil. If we’re to have any hope of coming together, we need to understand the psychology of what really divides us.

Victims and Villains

When we think about political polarization, we often think that what divides us is hatred and animosity. But it’s quite the opposite—Americans are divided by their perceptions of threat. Our moral and political beliefs are rooted in a desire to protect ourselves, our loved ones, and the vulnerable from harm. The problem is that we disagree about which threats are most pressing and who is most vulnerable to harm.

Consider immigration. Liberals might see undocumented immigrants as victims seeking a better life, and therefore support easier pathways to citizenship. Conservatives, on the other hand, might worry about crimes committed by undocumented immigrants against more vulnerable American citizens, and therefore support stricter borders. We all care about protecting victims from harm, but we emphasize different victims.

We all know that we want to prevent harm, but it’s harder to see that our opponents share the same concern. Instead, they seem more intent on dishing out harm, by voting against us and undermining our vision for society. Our opponents seem threatening to our way of life, and they seem like villains. They even seem like Hitler.

A recent study (not yet published) by Samuel Perry asked participants to place Adolph Hitler on a political ideology scale ranging from 1 (Extremely Left-Wing) to 10 (Extremely Right-Wing). Unsurprisingly, few people pegged Hitler as a moderate. But more surprisingly, there was substantial political disagreement about whether the leader of the Third Reich was left-wing or right-wing. Three-quarters of liberals said that Hitler was as right-wing as possible, but nearly half of conservatives said that he was as left-wing as possible. Though Hitler’s ideology might not map cleanly onto the modern American political spectrum, people on both sides conveniently think that he shared the beliefs of their political opponents. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. About 75% of liberals say that Hitler was extremely right-wing. About 50% of conservatives say that Hitler was extremely left-wing.

This general trend held when asking about other historical villains as well. Many liberals rated Joseph Stalin, the former dictator of the Soviet Union and leader of the communist party, as being a right-wing extremist. Of course, our opponents are not like Hitler or Stalin, but we see them as lacking a basic moral compass.

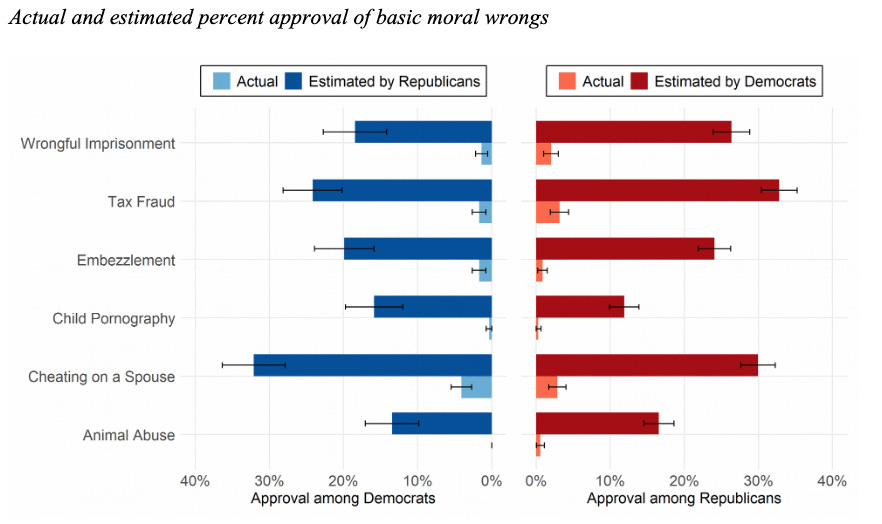

In a recent set of studies, a former Center postdoc Curtis Puryear asked Democrats and Republicans for their views on a range of uncontroversial moral wrongs, like child pornography, animal abuse, and embezzlement. He then asked them to estimate the portion of their political opponents that approved of these acts. He found that Democrats and Republicans estimated that between 10 and 30% of the other side approved of these blatant moral wrongs, when virtually none did. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Democrats and Republicans vastly overestimate the percentage of the other side that approves of blatant moral wrongs.

If 30% of the country cheered for child pornography and animal abuse, the future of America would be bleak. But there's a reason that political debates don’t center around these issues—they are condemned pretty much universally.

Many people are frustrated and tired by these examples of “false polarization”—political differences that only exist in our heads—because these imagined differences create real feelings of animosity. One reason these misunderstandings are so frustrating is that they seem so easily corrected. Imagine running into a liberal or conservative colleague at the water cooler and saying “hey, thoughts on animal abuse?” They would obviously say it was wrong. One of the biggest reasons that we fail to recognize our common humanity is that we simply don’t talk to one another.

Having the Right Conversations with the Right People

Many people have bemoaned that Americans are shying away from important political conversations. And this is true—almost half of Americans have given up on talking politics with at least one person, and people are increasingly self-censoring their political views for fear of backlash.

Part of the problem is that we are increasingly politically segregated. Americans have few friends who support the opposing candidate, which means that our political conversations are not playing out between well-meaning friends, but on national stages between political elites who are more likely to have nefarious goals.

The thing is, we need to be having these conversations. A pluralistic democracy requires that we interact with people who disagree with us, find compromise, and see each other’s common humanity. Seeing the other side as evil gives us an easy out—“we don’t engage with the enemy”—but it’s really bad for the health of our society.

And as it turns out, these tough conversations go better than you might expect. As work by Juliana Schroeder and Nick Epley shows, conversations with strangers tend to be more rewarding than we predict, because we underestimate how willing others are to talk with us (again with the misconception!). It is even easier to have conversations with co-workers; we never come away from talks at the water cooler thinking “that monster must love abusing animals.” Instead, we’re likely to appreciate our shared humanity.

Political identities can be explosive, but we need to connect with each other as people, not partisans. People mostly care about the same common needs—they want to have food on their table, be happy and healthy, and not have to worry about their safety. Despite what conflict entrepreneurs tell us on national TV, our commonalities far outnumber our differences.

I often think back to the road rage incident that we began this post with. At the time, I was so utterly convinced that I was in the moral right, and the other driver was the bad guy. It took years of distance and a PhD in social psychology for me to finally understand his point of view. I do not condone his violence, but I do recognize that he had very legitimate reasons to feel upset and victimized, and that these feelings caused his behaviors. Unfortunately, America doesn’t have years to fix our growing political divisions. But we do have opportunities, every single day, to make good faith efforts to understand each other.

Another interesting one. I can see same happening in India too. One way to reduce conflict is design festivals where people meet and expose to shared joys other than political ideologies.

This is an excellent read, Kurt! What you and Sam are doing can be a game-changer for political strife in our country. I remember reading “The Righteous Mind” around the first Trump election, hoping to understand the “other side”, especially since I knew people in town, and even my own brother who was a member of the other political side. I wanted to understand their position. These were intelligent people, and one was even raised in the same family and by the same parents as me. How could we have such different political views? I read the book mainly because I did not want ro see the other side as a villain, or demonize them for their beliefs. I truly was seeking to understand them. I feel that our country has gone way too far, since then, by demonizing the “other”. THIS read, and your theory of harm is for me, much more understandable and relatable! It makes me want to sit down and ask someone on the other side what their personal experience has been that has brought them to believe what they believe. It makes me want to have those conversations on a more intimate level, and it makes me want to really listen and learn. This, I believe will bridge divides. politicians want us to demonize each other. I think that is irresponsible! If we can start having conversations with each other, we can wield so much more power with our votes. Thank you for your work! It has the power to positively affect the way we relate to one another! Kudos to you AND Sam Pratt!