The Myopia of Heroism

Hamas, Israel, and the Quest to Save Victims

Towards the end of every superhero movie, there’s a showdown: the hero battles the villain, who is holding innocent victims hostage. Often set in some major city, the fight captivates the attention of both the audience and the fictional citizens, who look on in terror.

The fight inevitably causes massive damage to the city. Buildings and bridges full of people collapse into rubble. The ultimate conclusion of these movies is preordained: the hero vanquishes the villain and saves the victims.

The hero is always praised by the citizens, despite the massive collateral damage. By choosing to fight the villain—smashing into buildings and wrecking bridges—the hero likely caused the deaths of thousands of people. All these deaths just to save a handful of vulnerable victims?

Strangely enough, we never think about it like that. Instead, we watch the film through a kind of moral tunnel vision: victims need our saving, costs be damned. We call this thinking “the myopia of heroism”: when we set our sights on a clearly suffering victim, our moral concern for others is dampened.

It would be one thing if the myopia of heroism only happened in the safety of our local movie theaters, but it also alters our judgments in the real world. The myopia of heroism is why we embark on humanitarian interventions that sometimes do more harm than good, and explains our compulsion to do whatever it takes to save the vulnerable within deadly conflicts.

In this article, we’ll explain this myopia—how we cause others to suffer not because we are callous but because our compassion is hyper-focused. As we’ll see, this myopia is rooted deep in our moral mind, and understanding it can help us better grapple with complex conflicts like the current war between Israel and Hamas.

The idea that we sometimes care too much about the suffering of victims might sound strange at first. The way many public intellectuals put it, the world’s problems come from our failure to empathize with others. But this narrative is only half true. In reality, we often neglect the suffering of some because of our genuine concern for others.

The Drowning Child

In a famous thought experiment, the philosopher Peter Singer invites you to imagine that you’re walking to work when you pass a child drowning in a shallow pond. There’s no one else around, and if you don’t wade in and rescue them, the child will surely die. Unfortunately, doing so will ruin your fancy new suit. The question Singer poses to you is, “What do you do?”

You run in and save the child, of course. What kind of moral monster would choose a suit over a child? But Singer uses this example to flip the script—he argues that, as a matter of fact, most of us are that monster. Every year, millions of people die from easily preventable poverty-related diseases. And yet we buy ourselves new clothes and eat out at restaurants when that money could be used to prevent others from dying.

Intellectuals use Singer’s scenario to show how unprincipled we are in our concern for victims. Unless a suffering victim is staring us in the face, we find it hard to muster up the compassion to help them. But this misses the other half of the story: the crazy things we will do when we have a clear victim in our sights.

Let’s imagine a similar scenario with a twist. Instead of walking past a pond, there’s a dam, and by its gate, a child is pinned down by the current. No one else is around, and the only way to save the child is to open the dam’s gate, draining the reservoir. The catch: doing so would flood the town downstream, destroying homes and causing more people to drown. Would you save the drowning child, even with the prospect of killing many more?

We all like to think we’d pass on this immoral tradeoff, but in reality, when we are face-to-face with a clearly suffering victim, we become morally shortsighted. We neglect the potential suffering of other innocents as we focus on the compulsion to save the obvious victim. As with the superhero who destroys the city to save the hostages, the true consequences of our actions only become clear in hindsight.

The Dark Side of Good Intentions

The myopia of heroism is on prime display in foreign policy interventions, where well-intentioned fights against villains often cause collateral damage. In 2013 in Syria, that villain was infamous: ISIS. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the most feared radical Islamist extremist group, expanded into northern and eastern Syrian territory in 2013 and 2014, leaving horrific atrocities in its wake. ISIS massacred ethnic and religious minorities, sent suicide bombers into markets and urban public spaces, and beheaded members of the community over the slightest disobedience to Sharia law.

The United States and its allies heard victims of ISIS crying out for help and felt that they had no choice but to intervene. They launched “Operation Inherent Resolve,” an aggressive coordinated mission that successfully broke the reign of terror that ISIS held over the region but ended up leaving the country completely destabilized. The U.S. government levied harsh economic sanctions that suffocated ISIS and other bad actors from international support but left Syria in financial ruin, devastating the middle class—a major potential stabilizing force for a country in turmoil. Perhaps worse, the U.S. conducted over ten thousand airstrikes in Syria, leaving the country’s infrastructure in a post-apocalyptic state. The first responder team tasked with cleaning up the rubble of the city of Raqqa (pictured below) estimated that the civilian death toll of this particular airstrike was likely multiple thousands of innocent people. While it’s impossible to know what the human cost of non-intervention would have been, the civilian death toll is often overshadowed by reports of a successful heroic mission.

Figure 1. Rubble from an American airstrike in the city of Raqqa, Syria.

The image of rubble will strike a familiar note for those following the ongoing situation in the Gaza Strip. On October 7, 2023, the Islamist militant group Hamas launched a series of coordinated attacks on bordering Israeli towns, killing roughly 1,300 civilians and capturing at least 150 hostages (these numbers will likely change as new information surfaces). The Israeli Defense Force promptly responded with a complete siege of the Gaza Strip, cutting it off from food, fuel, and electricity and launching a barrage of airstrikes that has crippled the territory.

Much of the world responded to the initial attacks by Hamas with outrage and sorrow, a sentiment that we share. While it remains unclear how Israel will proceed with their effort to save the hostages, what we do know is that when innocent victims are involved, the myopia of heroism is likely to influence thinking. In the wake of threats made by Hamas to broadcast the brutal murder of its hostages, the Israeli Foreign Ministry spokesperson Emmanuel Nahshon called for the “complete and unequivocal defeat of the enemy, at any cost.” With the civilian death toll from the Israeli airstrikes reaching multiple thousands at the time of writing this, many are wondering what exactly that cost will be.

In fact, some foreign policy experts suggest that Hamas’ intention may have been to incite the myopia of heroism in the Israeli response and use it to their own advantage. As Dr. Audrey Cronin reports in Foreign Affairs, nefarious groups in the past have strategically provoked their enemies by targeting innocents. When their enemies respond with indiscriminate force that kills civilians, the group publicizes these deaths in an attempt to undermine the enemy’s moral credibility in the eyes of its allies.

Others cynically argue that Israel’s response is rooted less in righteous indignation and more in opportunism, advancing strategic aims that stretch back decades: to fracture, polarize, and dismantle the cause for Palestinian liberation. On this account, it is Israel that is capitalizing on the myopia of heroism, using public condemnation of Hamas (and, by conflation, Palestinians) as a cover to pursue its geopolitical goals without global pushback.

In a conflict with such complexity and historical weight, we are in no position to speculate about which strategies are truly at play on either side. But social psychological research suggests that public support for the Israeli response is surely bolstered by the presence of the clearly suffering hostages. Two researchers at Cornell collected public opinion data asking Americans about hypothetical risky humanitarian interventions—military operations where experts warned about potential civilian casualties or economic disruption. They found that Americans were roughly 30% more likely to support these risky interventions when they were framed as moral missions—to save innocent civilians—as opposed to missions to further U.S. strategic interests. This finding demonstrates how the myopia of heroism makes negative consequences seem morally irrelevant. When victims are involved, people feel a compulsion to “do something” to help, even at great cost.

Optical and Moral Illusions

If we care so much about helping victims, why do we end up inadvertently harming many more? The myopia of heroism means that when a clear victim captures our focus, other victims fade from view. This kind of selective attention is a central feature of our moral judgments but is also deeply embedded in our perceptual system.

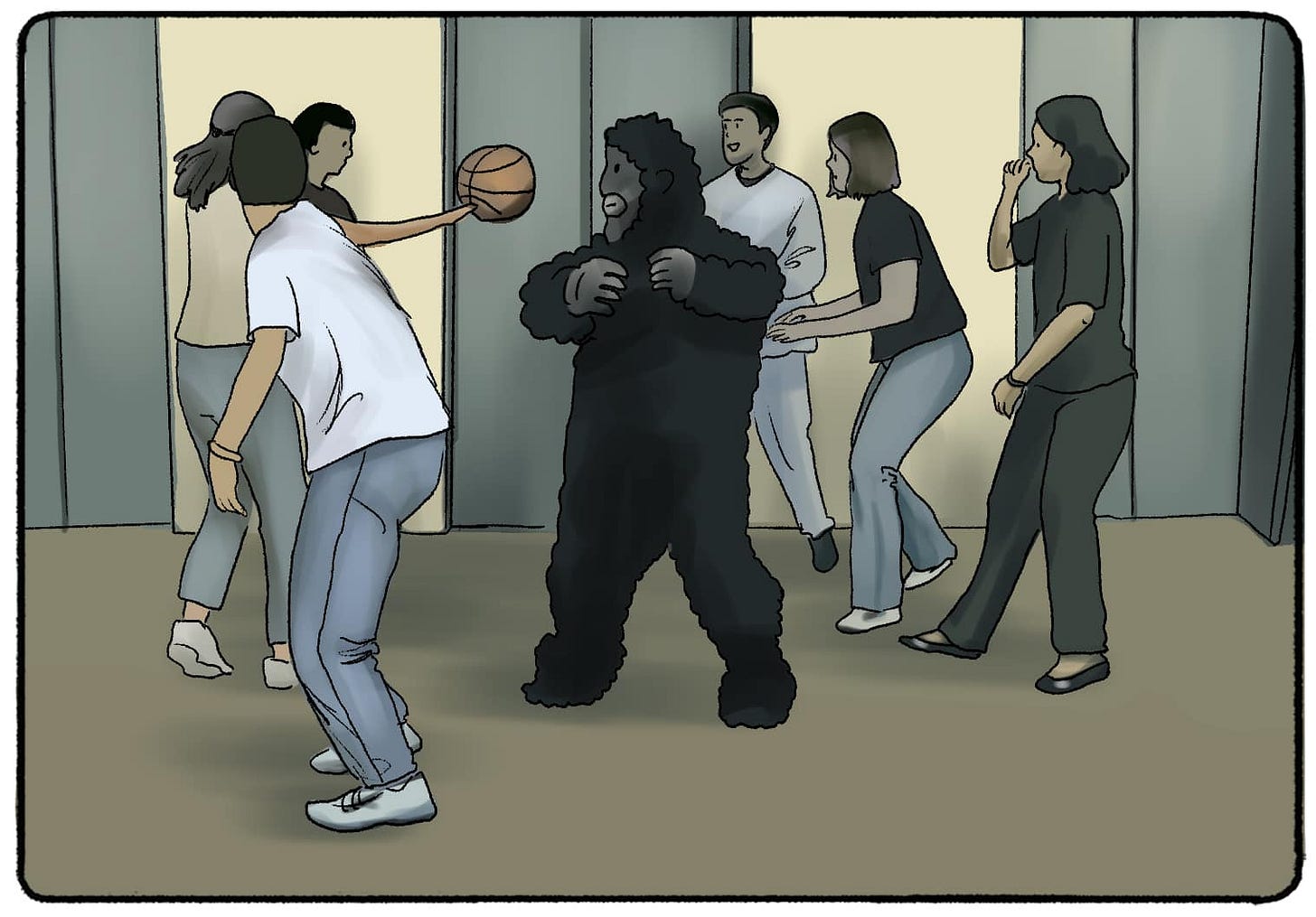

If you’ve ever taken an introductory psychology course, you’ve likely seen the classic “Invisible Gorilla” experiment. In this video demonstration of “inattentional blindness,” you’re tasked with counting the number of times a basketball is passed between a group of moving players. The task is so engrossing that roughly half of people fail to notice when a researcher wearing a gorilla suit casually walks across the screen.

Figure 2. The “Invisible Gorilla” experiment. When asked to keep track of the number of passes between players, half of people fail to see the person in the gorilla suit walk by.

Just as our attention can be monopolized, so can our empathy for others. This happened in 1987 in the case of “Baby Jessica” McClure. The 18-month-old was playing in her aunt’s backyard in Midland, Texas, when she tumbled 22 feet into an 8-inch-wide abandoned water well. She sat trapped in the narrow shaft for 58 harrowing hours as the nation watched the televised rescue effort in horror. Baby Jessica and her family were inundated with support, receiving an estimated $800,000 in donations—money that could have saved hundreds of suffering victims if allocated elsewhere.

The fact that clear victims tug at our heartstrings is widely recognized by humanitarian causes around the world. Charity campaigns garner support by advertising images of suffering children instead of statistics about anonymous victims, and animal rescue commercials force you to stare straight into the pleading eyes of abused dogs. Although the “identifiable victim effect” is well known, what is less publicized is how focusing on victims simplifies our understanding of complex moral situations.

A decade of research from our lab finds that our moral judgments all revolve around a common core: the perception of a victim suffering at the hands of a villain. This “cognitive template” is so powerful that it reduces the messiest moral situations to a straightforward pair of villain and victim. Of course, people often disagree about which groups should be considered the villains and victims in any given conflict, but these characters feel very real in the eyes of the perceiver.

Our moral minds are kind of like the storyboard for a superhero movie: we identify a clear villain and victim, and then we identify a hero to intervene—someone noble to vanquish the villain and rescue the victims. Once these three characters are selected, they drive the story and everyone else becomes an extra, even if they too are being harmed. We feel a deep compulsion to heroically help our highlighted victims, but the myopia of heroism can make us fail to appreciate the suffering of innocent others.

Figure 3. The Myopia of Heroism. Our mind locks on to a villain and a victim, transforming us into heroes and rendering other victims invisible.

Importantly, recognizing the myopia of heroism isn’t about blaming those who strive to do good. Soldiers who risk their lives to save suffering victims are undeniably heroic, and the desire to do whatever it takes to save innocent hostages comes from a noble place. But our deep gut-level concern for saving victims means that it can be useful to pause for a moment when we are considering how to act in conflicts, especially when the potential for collateral damage looms. Fortunately, there is a tool we can use to zoom out from our myopia.

Rational Compassion

In his book “Against Empathy,” the psychologist Paul Bloom argues that empathy is an unreliable emotion in the modern world. The emotional tug of empathy biases our judgments, leading us to favor close versus distant others and short versus long-term solutions. Bloom suggests that instead of using empathy to guide our decision-making, we should use rational compassion, pairing a concern for the well-being of others with reasoned assessments about how we can help them. Rational compassion requires that we contextualize our initial gut feelings by thinking through the costs and benefits of our actions when deciding who and how to help.

Central to rational compassion is the idea that it shouldn’t have to feel good for us to help others. In Singer’s thought experiment, we should save the drowning child not because our emotional reaction compels us to but because we know that it’s the right thing to do. Likewise, we should support far-away causes even when we don’t feel personally connected to them, because, in principle, everyone’s suffering matters.

At the same time, applying rational compassion means that no matter how much it feels like we should help a victim, we should at least pause to consider the broader picture—and other potential victims. This consideration may ultimately lead us to the same conclusion, but the important point is to remind ourselves that, deep down, almost all moral situations are more complicated than our minds initially assume.

A Final Note on Israel and Hamas

As social psychologists, we don’t claim to know the best path forward in perennial sectarian conflicts. And though we study the psychological basis of morality, we possess no special knowledge about how a country ought to respond to terrorism. We are hopeful that leaders, who are far better informed than ourselves, will make good-faith efforts to minimize civilian casualties. However, we do feel that it is important, as international observers, to understand the powerful processes that shape our moral judgments. In doing so, we can exercise greater self-awareness and better understand the perspectives of individuals on both sides of this conflict. In that regard, we would like to thank our Israeli and Palestinian friends who commented on early versions of this article—your personal stories and thoughtful disagreement greatly improved our thinking about these issues.

I think there’s a myopia of minimisation that this piece fails to take into account.

The continued existence of brutal regimes such as Hamas or ISIS will lead to more death and suffering in the long run. If it is a just cause to topple them, why are 5000 dead civilians now more important than 10,000 over ten years?

In general a more aggressive attitude can shorten a war and reduce the overall amount of casualties. It’s even more myopic to judge the myopia of heroism solely on the basis of the short term consequences.

I'll add that my former teacher wrote an extensive reply to some philosophical issues to be found here:

https://dailynous.com/2023/10/30/how-not-to-intervene-in-public-discourse-guest-post/

I agree with most of what he says, though I think he's downplaying the important aspect that we discussed here about the importance of goals in war to the discussion about means