The Psychology of Pettiness

Why (some) people get so angry at line-cutting and grape-stealing

A couple weeks back, I (Kurt) was grocery shopping with my kids. While in the produce section, I noticed a woman walk up to a case filled with bags of grapes. She opened a bag, took out a handful of grapes and began eating them. Without paying.

This person looked to be in her 30s—she was wearing a t-shirt with a cool band logo and was chatting with her friend as she ate the grapes. Outside of this encounter, I’m sure she was a fun, agreeable person. But here she was, committing pure evil, fraying the ethical fabric of society, destroying the moral order of the country—and in front of my children.

Initially, I gave her the benefit of the doubt. Maybe she was sampling the grapes? No. She didn’t even buy a bag. She was just stealing them. I had to shield my kids’ eyes from the carnage lest their developing moral sense become perverted…

The Geneva Conventions ban cruel and unusual punishment, but here I was thinking that this person deserved something creatively punishing. Perhaps in the spirit of Roald Dahl’s Matilda (with young kids, I watch a lot of kids' movies) she should eat grapes until she bursts (or at least becomes ill). Or maybe, à la medieval Europe, we publicly shame her by forcing her to parade around in a Welch’s brand grape jar, just like drunkards were forced to wear distillery barrels?

Figure 1. “The Drunkard’s Cloak”, a device used to shame people for public intoxication in medieval Europe.

I’m kidding, of course, but I’m not alone in thinking that some minor infractions deserve severe punishments. Inspired by this encounter, in our first lab meeting this semester we asked students, “What minor norm violation do you think should be punishable by death?” Apparently, most of us were filled with loathing about many minor infractions: Cutting in line, double parking, chewing loudly, walking slowly, texting during movies…the list goes on.

Why are many of us filled with righteous rage over inconsequential slights?

And what about the people who weren’t filled with rage? When I was checking out at the grocery store, I couldn’t help but relay what I had witnessed to my cashier—even if the grape-eater was now long gone. She just shrugged and said “sometimes people do that.”

When witnessing the same transgression, how can some people be pissed and others placid, like the two social media posts below? Some of us are ready to risk it all to punish a slow-walker, while others (like my cashier) could care less about unpaid grape sampling.

As it turns out, our desire (or lack thereof) to punish minor social transgressions has a deep basis in our moral psychology, and it hinges on the cultures we live in.

A Puzzle Across Cultures

Some cultures seem to really care about social norms—the invisible, often unspoken rules that govern our behavior—and are happy to condemn you for violating them. When I visited Japan, I was in a busy shopping district when I bought a donut and then ate it while walking down the street. Some shop owner stopped me and told me that I wasn’t allowed to eat while walking–the forbidden practice of "tabearuki" (食べ歩き).

Other cultures are much more lenient with social norms. Not only can you eat a donut while walking in the US, but some states (like Nevada and Montana) have no laws against public intoxication. On many American college campuses, it’s acceptable and even encouraged to carry around cans and Solo cups with alcohol. In American grocery stores, some people eat grapes without paying! This behavior definitely wouldn’t slide in Japan.

There is a term in cultural psychology for these differences in social strictness: cultural “tightness” versus “looseness.” Tight cultures (like Japan) enforce strong social norms and mete out strict punishments against norm-violators. Loose cultures (like the United States and many other Western nations) have more flexible norms, permitting a wider range of behavior based on the context. You can think of the tightness-looseness spectrum as a culture’s general tolerance for deviant behavior (for example, see the annual “No Pants Subway Ride” prank on the New York City subway, an odd-but-accepted behavior typical of a loose culture).

Stanford psychologist Michele Gelfand is the leading authority on cultural tightness (here’s her book on the topic), and her research shows that all nations can be classified along a tight-to-loose spectrum. Gelfand and her team surveyed people from 33 nations about the acceptability of performing various behaviors (e.g., arguing, eating, laughing, swearing, singing) in various public locations (e.g., in a bank, library, bus, or elevator).

They found that everybody’s appropriateness judgments hinged on the situation (even in a loose culture, it’s more acceptable to cry at a funeral than at work), but there were reliable differences in transgression tolerance across nations. The United States had a tightness score of 5.1 (pretty loose) compared to Japan’s 8.6 (pretty tight), and notably lower than Pakistan’s 12.3 (extremely tight).

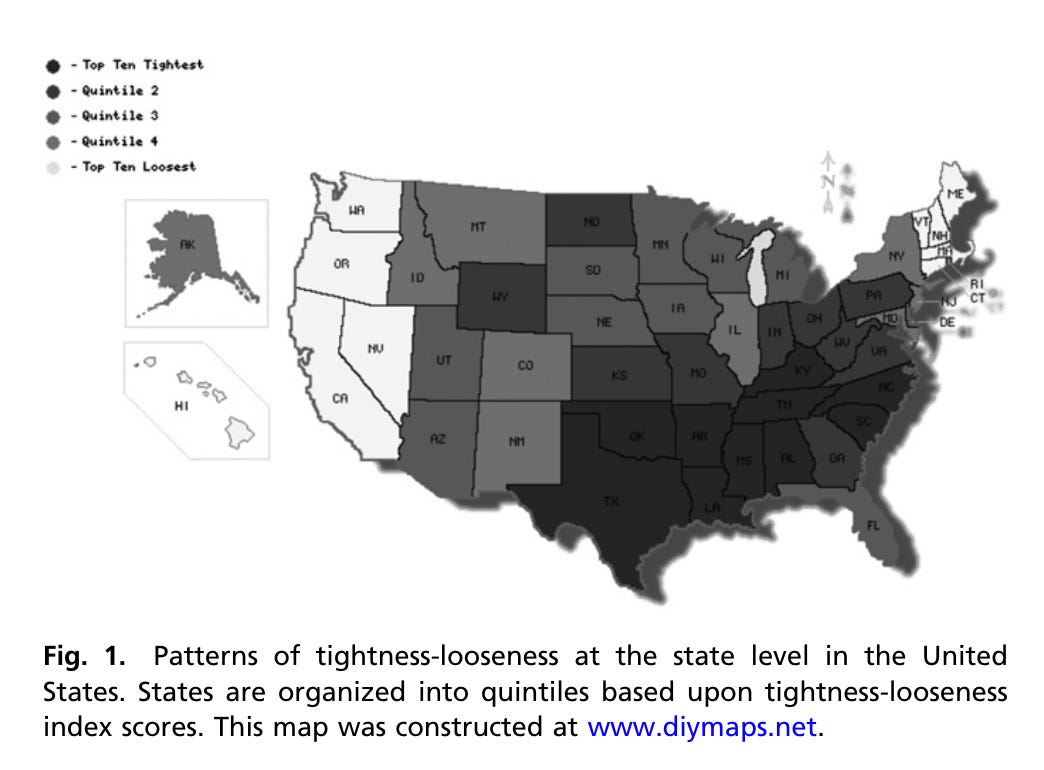

Though the United States is a relatively loose culture, another study found that even individual states differ on their degree of social strictness. The American South tends to be culturally tighter, whereas the West Coast and New England are extremely loose. Even in our progressive town of Chapel Hill, some kids attend cotillion—etiquette classes for middle-schoolers where they learn to respect social norms.

Figure 2. Patterns of tightness-looseness by state. How strict is your state? From Harrington & Gelfand, 2014.

Different people can also be tighter or looser about norms depending on their upbringing, personality, and subculture. You can take this questionnaire to find out where you fall on the tight-loose spectrum. I (Kurt) scored a 52/100, which is considered moderately loose, despite my outrage at unpaid grape eating and my conviction that there are definitely right and wrong ways to load the dishwasher. My wife, a very conscientious New Englander, scored in the 80s. She is much less likely than me to swear in faculty meetings.

It can be fun to look around at the different societal attitudes towards norm violations, but underlying these attitudes is a deep truth about morality: our need to cooperate and avoid threats.

The Grape that Broke the Camel’s Back

Morality evolved to help us cooperate. By pushing us to suppress our selfish desires for the good of the group, morality helps our societies succeed and wards off the threat of anarchy. Society would crumble if everyone was selfishly stealing each other’s resources and exploiting each other for their own benefit, and so we developed strong norms that prohibit antisocial behavior.

Moral outrage—our feelings of anger and contempt at the wrongdoings of others—makes us care about and enforce these social norms. The most moralized of social norms involve obvious harm, like physical violence, because the spread of physical violence would destroy society. But some of us moralize social norms that seem less obviously harmful, and less obviously likely to cause social destabilization.

From the perspective of “morality as cooperation” theory, these minor norms can be important because they also help people cooperate. When everyone stands only on the right side of an escalator (as in the beautiful picture below, Figure 3), it leaves the left side completely free for people in a hurry to walk.

Figure 3. Even NYC subways can have a “tight” culture: A crowd following unspoken “lane” etiquette on the subway: standing on the right, walking on the left.

Although everyone might appreciate being able to make it to work on time, there are times when coordination really matters: in times of threat. If there’s a fire, it’s important that everyone moves calmly and orderly toward the exit. Likewise, if food is scarce—as it was during World War II—it’s important for society that everyone waits their turn for their allotment of bread and sugar, rather than jumping the line and looting.

According to Michele Gelfand, whether a place or a person is tight or loose depends on the extent to which they face threats in their environment. In her analyses (both cross-national and within individual states) locations with the tightest cultures tended to be those that faced the highest amounts of ecological threats, like famines and natural disasters. Cultures in which people have to quickly work together in the face of danger are cultures that moralize even relatively minor norms.

For example, Japan is extremely earthquake-prone, and also has a relatively high population density, which makes proper coordination even more essential. In contrast, places like Montana and Nevada are relatively unthreatened by natural disasters—and have a spread out population—and so they can be looser. People can live however they want to live because fine-tuned coordination is less essential for the survival of their society. The threats we faced throughout our history leave a lasting mark on the types of behavior we tolerate from our neighbors.

Slippery Slopes: A Grape is Not Just a Grape

The psychology behind tightness-looseness shows that my lab’s irritation over minor offenses isn’t just about small social slights. Grape eating isn’t just grape eating. Our moral outrage is not just about the behavior itself, but about what it might portend for society.

Texting in movies or cutting in line are more than just annoying to the people who condemn them; they represent a descent into social decay. If it’s okay to snack on unpurchased foods, what’s stopping you from stealing the food straight off the shelves? If you jump the line at an amusement park, would you jump the line when we are waiting for our meager allotment of food in a famine? Will my kids go hungry because of your selfishness?

There is lots of evidence to suggest that our moral outrage is attuned to detect harm, but harm isn’t always cut and dry. Some acts have a potential for harm, like drunk driving. We recognize that even if you don’t hit someone on a drunk drive home from the bar, it’s still a bad thing to do.

Other acts make us outraged because they would cause harm if everyone did them. Dropping one piece of trash might seem minor in isolation, but if everyone littered, we would be swimming in a sea of trash. In philosophy, this is called the “logic of universalization,” and there is evidence to suggest that people use this logic when deciding which acts are morally permissible.

And finally, some acts seem to provide a slippery slope into greater harms, like panic around “reefer madness”, when it was argued that smoking weed would eventually lead kids into violence, criminality, and satanic cults. Without substantial evidence, the slippery slope argument is considered a logical fallacy, but Gelfand’s research suggests how even minor coordination norms can be important for societies in times of crisis.

I’m surely overreacting about the grapes. But understanding the psychology behind when and why we condemn minor norm violations is important for making sense of moral debates. What might seem like a harmless indulgence to one person can seem more dire to another. The question of who is “right” or “wrong” may have no objective answer, but science suggests that tightness and looseness both have their appropriate place, depending on the existing level of threat in our society—and in our minds. If you’re the kind of person who fixates on danger, you might see every grape-eater and double-parker as a harbinger of doom, but if you’re chill and laid back, you might just see them as people who are hungry and too busy to park correctly.

Which kind of person are you?

Thanks for introduction to the tightness-looseness culture. Actually, this is one of the important reasons for my mother immigrating to the U.S. because her openess to new experiences is considered against the normal ways of living accroding to her friends in China. Interestingly, from time to time, she complains about many U.S. colleagues regularly breaking work rules and regulations.

Besides, when I am doing questionnaire evaluating the level of tightness-losseness, I found many items are about "self-discipline" and "tolerance to uncertainty". I am not sure if they have construct validity problem as I assume self-organized according to rules and routines set by the individual themselves may not necessarily relate to the conformity/obedience to norms set by the culture and society. There are many very oragnized persons around me who are used to doing reflections systematically on the norms people surrounded take granted to. Take the interesting example of dishwasher^_^: there exist good and bad ways to load dishwasher, but the way indicated by your mother or the instruction book might not be the best one.

For me, I scored 56 as moderately loose. I consider myself strictly following the rule and regulations when they are justifable (like just laws to prevent harm, or rules of a card game to keep the game going), esepcially when someone explains the rules and their reasonings beforehand. However, I am very doubtful when norms are debatable, esepcially when someone impose norms on others without offering persuasive reasonings (e.g., you should get married because this is what most people do). Therefore, I may be a weird case to put into the binary classification.