When a Christian Nationalist Drove Me to the Airport

Why Civility is Not Surrender

"I'm a Christian nationalist, but not the normal kind," said my Uber driver. We had 30 minutes left until we arrived at the airport.

I find myself in political conversations with strangers all the time. It's a hazard of the job. When people ask me what I do, I start by saying "a psychologist, but not the helping kind," which dispels the idea that they should tell me about their childhood relationship with their mother.

I then say that I'm a researcher who studies morality and politics, which unlocks a different kind of outpouring—less sadness about their relationships and more outrage about the world these days. People tell me what they believe and then tell me how other people get it wrong.

I live in a purple state (North Carolina)—in a very progressive town next to a liberal university surrounded by conservative countryside—and so the people I meet have all kinds of positions. I've chatted with everyone from a big-bearded communist who believes we should abolish private property, to a retired UNC employee who believes that Biden was the worst president of all time, to the Christian nationalist who kicked off this post.

After he told me "I'm a Christian nationalist, but not the normal kind," I wondered what to do. Surely, he would espouse some view I disagreed with, and disagreement is uncomfortable. And then what? If we argued, he might get angry. Who knows, maybe he’d even drive off the road in rage, or kick me out and I'd miss my flight.

Then again, I study how to have better conversations across political divides, and here was a chance to practice what I preached. I knew the tips well enough to write about them in my upcoming book Outraged, and I felt I should put them to use. I was also genuinely curious about what he believed. Here was a chance to learn something new about morality and politics, from someone who believed something different from my academic friends.

But how could we have this conversation with civility? The number one tip I've learned from my research and collaborations with conflict resolution practitioners (like Essential Partners) is to strive for understanding: make it clear that I want to learn about what they believe, rather than win some debate. This is the reason this newsletter is called “Moral Understanding.”

Finding Moral Understanding in an Uber

To have a respectful and meaningful conversation, I needed to express my desire to learn. Doing so was simple enough: I just asked him "how are you different from the typical Christian nationalist?" What did he believe?

He told me he was more economically libertarian than most. He said that he believed—like other Christian nationalists—that America was founded as a Christian nation and so it should have the official religion of Christianity, specifically evangelical Protestantism. He said that you could practice other religions: "You can be a Muslim, and you can go to a mosque, but you shouldn't be able to advertise it in the public square." No signs. I didn't ask whether women could wear a hijab in public because he was on a roll.

He also believed that there were 3 supreme human authorities in the country: Church leaders (who oversee the spiritual health of the nation), the president (who makes policy decisions), and the father of the household (who decides everything within the house).

He said that we should loosen regulations related to job requirements, a standard libertarian position. If he wanted to start a small business to better support his family, why should he have to pay taxes and go through all this red tape? The government was going after Uber and they should stay away because Uber was helping him earn money.

I nodded along, asking clarifying questions, and it was clear that he felt heard, perhaps for the first time in a long while. Conversations about politics can often seem like a chance for people to brush aside what the other person says and launch into their own tirade. I'm sometimes guilty of doing just that, but I was trying hard to wear my social psychologist hat.

It turns out that asking follow-up questions is a great way to showcase your receptivity to other people's ideas. For example, in one study psychologists tasked 430 participants with getting to know a stranger online. They instructed half the participants to only ask a few questions about the other person (no more than four) and instructed the other half to ask a lot of questions (at least nine). For example, if someone in the conversation said, “I’m really into rock climbing,” someone in the “few questions” condition might say, “Cool, I’ve never been rock climbing,” whereas someone in the “many questions” condition might say, “Cool, how old were you when you started?”

The researchers found that people thought their conversation partner would prefer that they ask fewer questions—it’s a conversation, not an inquisition!—but this intuition was wrong. In reality, participants liked their conversation partners more when they asked lots of questions—especially follow-up questions like “Could you tell me more about that?” because it demonstrates genuine interest in what the other person is saying. (Asking questions also helps you get a date; in another study, the researchers found that those who asked more questions at a speed-dating event got more invitations for a second date.)

I wasn’t looking for a date with my Christian nationalist Uber driver, but asking him about his views showed him that I was genuinely curious to learn more. And to be honest, hearing more about his views (though I disagreed with many of them) was fun.

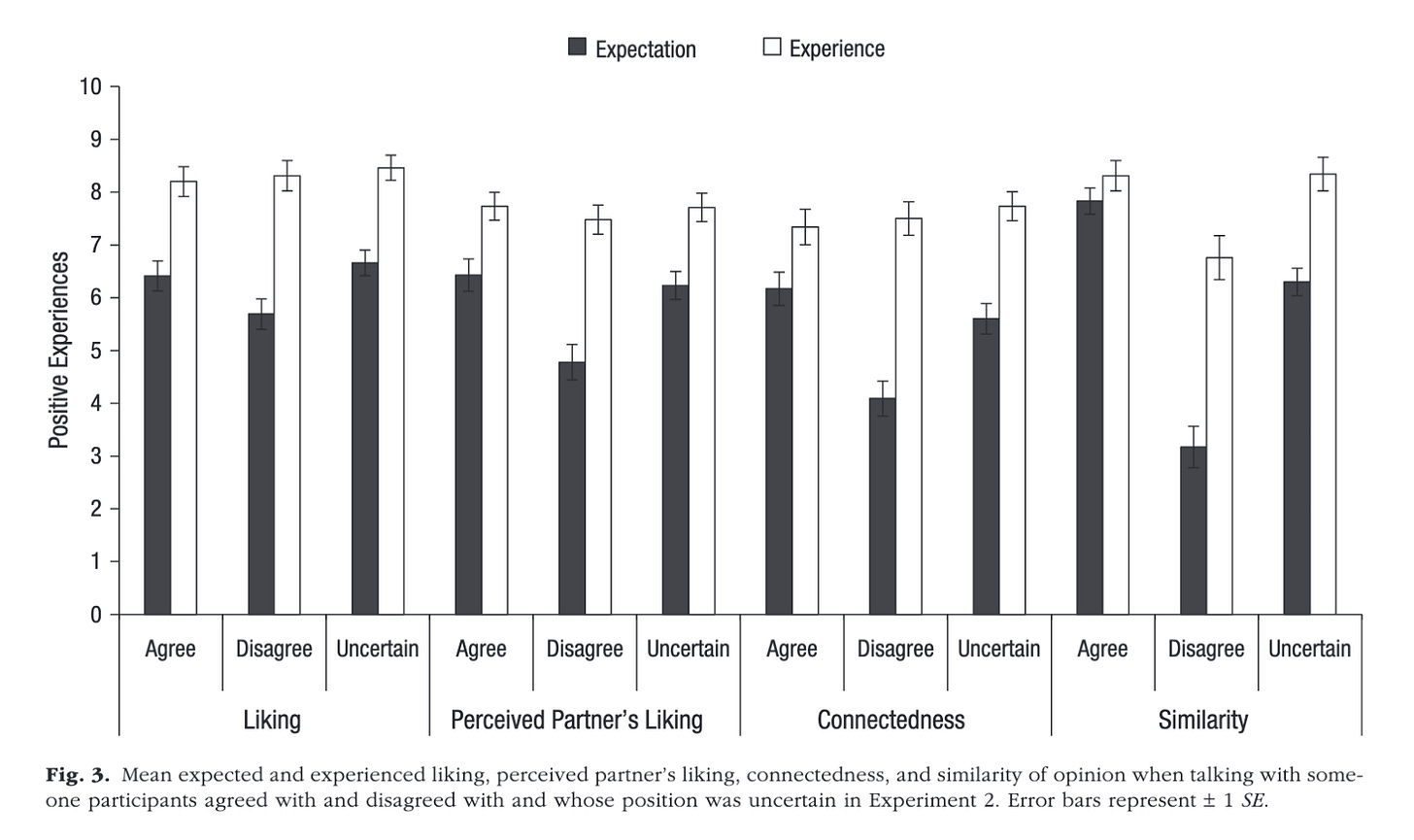

Many people dread even banal conversations with strangers, let alone political conversations, but it turns out that even conversations about politics tend to be unexpectedly positive. This was shown in one study where researchers paired participants up to discuss hot-button issues (like religion or abortion) with people who disagreed with them. Before the conversations, most participants predicted that they would go pretty poorly, ending in shouting matches or awkwardness. But after they had the conversations, participants reported that they felt much more connected and even found unexpected points of common ground.

Figure 1. Political conversations are unexpectedly positive. From Wald et al., 2024.

Of course, having political conversations isn’t just about finding points of agreement. Just because you’re trying to understand doesn’t mean that you have to be a door mat, submitting to whatever they say. The idea that you have to give up your convictions to talk respectfully about politics is a common misconception.

Civility is not surrender. In fact, it allows you to push back better against ideas you disagree with, because you actually understand what you are pushing back against. And if you’ve done it right, your conversation partner will respect you for pushing back because you've established respect.

Here's some anecdotal evidence. Later in our conversation, when I felt we understood each other, and when my Uber driver learned that I study how to better navigate political divides, we started talking about abortion. He told me that he was pro-life and considers abortion to be murder. I mentioned that evangelical Christians weren’t always pro-life (a topic we discuss in another post). As recent as the 1960s, they believed that moral status was conferred not by conception, but by birth. This position helped distinguish themselves from Catholics and was seen to be consistent with theology.

He replied that history is full of evil moral positions and started talking about the Holocaust, comparing pro-choicers to Nazi architects of genocide. This was not a surprising conversational transition. As I mention in Outraged, Godwin's law argues that as conversations about politics draw on (at least on the internet), the probability that someone mentions Hitler approaches 100%.

Here's where I pushed back. As we exited the highway, I paused the conversation. I said that part of having a respectful dialogue means that you can't caricature one side or the other as being deeply evil. And likening one side of a moral debate (where clearly compassionate people exist on both sides) to the Holocaust is not a good faith argument, no matter how strongly we feel about our convictions.

And to his credit, my Uber driver nodded and apologized. He said he wasn't trying to make anyone seem like Hitler, but was trying to highlight the potential slippery slope of decisions about life. If we ignore one source of suffering, he said, we might be more likely to accept other forms of suffering. I mentioned that many people who are pro-choice don't want to end anyone's life, and instead see their position as protecting the lives of mothers. We are all doing our best when it comes to messy tradeoffs about harm and protection.

It was clear he still disagreed, but we were pulling up to the airport. He thanked me for listening and for the conversation. I thanked him in return, and thought of another piece of wisdom I learned from John Sarrouf, a co-director of Essential Partners. John told me that these conversations are messy and that it is challenging for people with strong feelings to translate their complicated convictions into words, especially when they are used to attacking and being attacked.

We have to give people some grace to express their beliefs, and when we give people grace, they often give it back to us. This is why asking clarifying questions and seeking understanding is so important. What people initially say might not really be what they believe, especially if you push them on it.

The quest for civility does not make you a moral coward. Rather, striving for understanding and affording your opponent respect can allow you to push back more, making clear that compassion and assertiveness can co-exist in a moral conversation—rather than cheap hyperbole and ad hominem attacks. By enforcing guardrails in the conversation—and making sure you stick to them—it allows everyone to feel heard, and at the end of the day people often realize that our divisions are not as strong as we thought.

that's what I call good worlding

What an interesting conversation. I appreciated your perspective around the balance between compassion and assertiveness, and how one does not negate the other. I'm sure you go into more detail elsewhere, but thinking of this specific conversation, I'm curious on your thoughts (and the research) around the idea that "civility" is granted more towards certain people than others (i.e., people who look like you), and that being "civil" is policed differently in different communities. In addition to your curiosity about this person's positions and desire to engage in a more meaningful discussion of their political views, I imagine they felt they could be more open with you (and respect your differences of opinion) because you weren't, say, a woman.