Why Grandma’s Cookies Taste So Good

Or: When I Gave Electric Shocks to Harvard Undergrads

My Grandma Ellen was known more for drinking Vodka than for her cooking, but when I went to visit, she made cabbage rolls in tomato sauce. I hate cabbage rolls, but these ones tasted pretty good. Why? Not because she was a good cook. They tasted good because I appreciated the intention behind them—the kindness I saw behind them changed my physical experience of them.

Whether we perceive others as having good intentions has a huge impact on our day to day experience. This really matters for our political moment because, unlike my grandma’s unpalatable cabbage rolls, we almost always infer the worst intentions in people who vote differently. This not only makes their words and deeds seem worse but can also cause us more discomfort—and perhaps even more pain, just like the time I shocked Harvard undergrads in grad school.

The Big Idea: The key idea of this post is that—because we are social creatures—how we experience the world hinges on the intentions we see behind events. Perceived benevolence makes everything seem better, but perceived malice makes everything seem worse.

The Power of Perceived Intentions (Shocking Harvard Undergrads)

Our assumptions about people’s intentions powerfully shape our everyday experience. When our friend says “nice hair,” we think it a sincere compliment, but when our nemesis says the same thing, we think it a sarcastic barb. In graduate school, I published a paper showing that perceiving good intentions—as opposed to bad intentions—can soothe pain, increase pleasure, and even improve taste.

Many folks here will know about the classic Milgram shock experiment, where an experimenter in a white coat can get participants to ostensibly shock someone to death with only polite insistence. Social psychologists can no longer get people to shock each other (due to modern ethics boards), but we can still give people shocks, as long as they are uncomfortable but not too painful.

Under the (true) guise of learning how “interpersonal perceptions” shape experiences, I hooked up undergrads to a shock generator and told them that another person (who was actually a research assistant accomplice) would be choosing to give them one of several different tasks, like counting dots or looking at colors.

The key trial was when the accomplice chose between giving them a shock (rate its discomfort) versus a series of tones (rate their pitch). More often than not, the accomplice chose to give them a shock. From the participant’s point of view, this was maliciously intended. Why are you choosing to shock me when you could choose something else?!

Importantly, there was another non-malicious condition. In this condition, we told the participants that we had secretly switched the research assistant’s choice of task. So if they had intended for the participant to receive “task A,” they would get “task B.” In the key trial, the accomplice chose “tones,” which meant that the participant actually received “shocks.” So rather than being maliciously intended, the shock was accidentally given. Did this change how much the shocks hurt?

The voltage of our electrical zaps were held constant, and so we might expect the physical experience of pain to be the same. But this wasn’t the case: participants reported feeling less pain when the shock was accidental compared to when it was maliciously intended. When there is malice behind something, it physically hurts more. The same is likely true of slaps and insults—when things are intended cruelly, they cause us more suffering.

Perceived malice shifts our experience of the world, but might also perceived benevolence (like my grandma’s cabbage rolls)? Does kindness make us experience things as nicer?

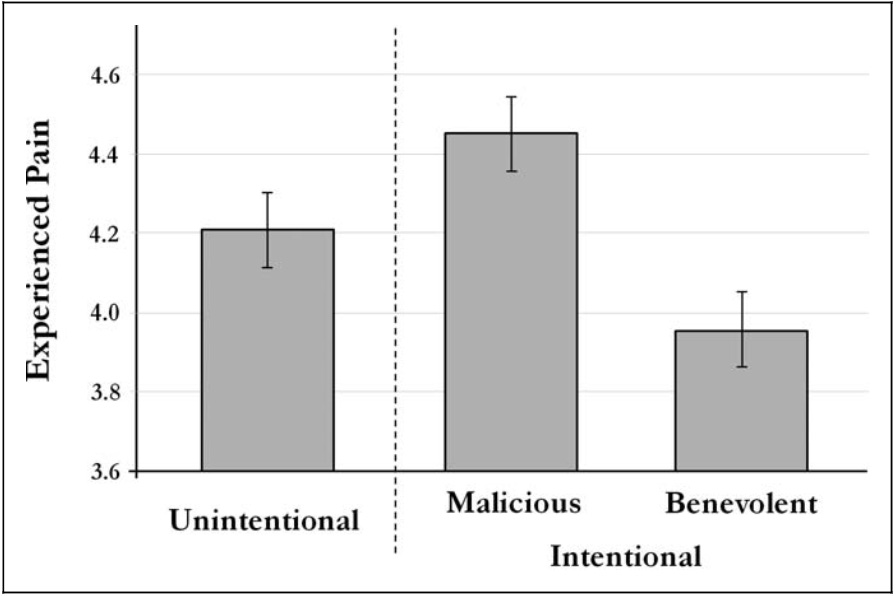

I ran another shock study using a similar methodology, but I added a condition where participants believed that the accomplice chose to shock them because it entered them into a lottery to win $50—they had their best interest at heart! I found that benevolently intended shocks hurt even less than malicious or unintentional shocks, despite the voltage being the exact same (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Electric shocks hurt less when they have good intentions behind them. From Gray, 2012.

In a final experiment, research assistants handed out goodie bags filled with a selection of candy. Each bag contained a note indicating that the candy was either carefully curated (“I picked this just for you. I hope it makes you happy.”) or chosen at random (“Whatever. I don’t care. I just picked randomly”). The actual candy was the same, but participants reported that it tasted physically better—and actually sweeter—when it had the added benefit of good intentions.

Perceived intentions really do change experience. Grandma’s cookies (and cabbage rolls) taste better than store-bought cookies because we know they were made with love. And when it comes to politics, perceiving good intentions can lower the temperature on our outrage.

The Destruction Narrative (Better Replaced with the Protection Narrative)

We usually assume the worst intentions in politics. In my new book Outraged, I argue that we tend to view our political opponents through the “destruction narrative,” assuming (incorrectly) that they’re mostly motivated by hate and a desire to harm and destroy. In contrast, we think our side is motivated by love and compassion. They are malicious, we are benevolent.

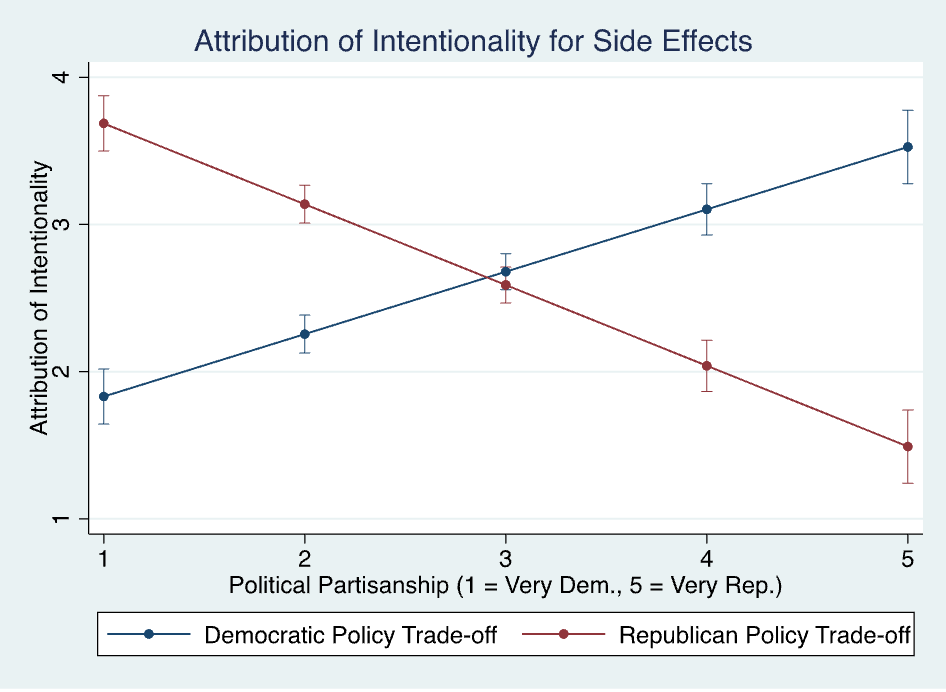

Supporting this idea, one of our lab’s collaborators, Dr. Daniela Goya-Tocchetto, conducted a study on the “partisan trade-off bias,” finding that people often assume malicious intent in their political opponents. Daniela and her colleagues asked Democrats and Republicans to consider some controversial government policies on taxation, gun control, environmental protection, and voting rights, passed either by their party or the other party.

Like any policy, these policies had tradeoffs, trying to achieve some good but bringing about some negative consequences. Importantly, these negative effects are usually unintended and often regretted. For example, when Democrats lobby for tighter environmental regulations to protect ecosystems and prevent climate change, they regret that blue-collar workers in the fossil-fuel industry will lose their jobs. Likewise, when Republicans support plans to ease environmental regulations in order to boost the economy, they don’t celebrate the image of baby animals being crushed by heavy deforestation machinery.

In Daniela’s study, when people thought about their side’s policy preferences, they tended to view the negative tradeoffs as unintentional: their political leaders didn’t want to cause suffering and were trying to make the best of a tough situation. But people thought that politicians on the other side wanted to cause suffering—that these harmful side effects were not side effects at all, but were instead an intentional consequence of their malicious agenda (see Figure 2).

Republicans thought that Democrats wanted tighter environmental restrictions so that they could destroy working-class jobs, and Democrats thought that Republicans wanted looser regulations so that they could speed up the collapse of our natural ecosystems. And when we assume the worst in our opponents, it becomes very difficult to find common ground, or to even have a civil conversation about policy. A person who makes decisions with the goal of killing innocent animals is not worth talking to, nor is someone who hopes that middle-class families lose their income.

Figure 2. Democrats and Republicans view the unintended negative side-effects of the other side’s policies as being intentionally caused. From Goya-Tocchetto et al., 2022.

But luckily, the destruction narrative isn’t true. Rather than the destruction narrative (“they want to burn it all down”), people are acting to best protect themselves, their families, and the vulnerable—the Protection Narrative. In fact, research in political psychology shows that when it comes to people’s voting behavior, we are more motivated by love for our side—compassion, empathy, and a desire for belonging—than by hatred for others (see studies here, here, and here).

Giving Others the Benefit of the Doubt

When it comes to politics, perceiving good intentions in others—by giving them the benefit of the doubt—can make the difference between a productive conversation and a shouting match. At the very least, it’s helpful to stop our knee-jerk reflex to see the other side as motivated by malice. When we resist the “destruction narrative” the clumsy comments of the other side hurt us less.

Of course, some people really do have bad intentions. It’s unlikely that conflict entrepreneurs and online trolls have your best interest at heart when they stoke outrage about politics. But according to my lab’s research, everyday people form their beliefs based on genuine concerns about protecting people from harm, not based on a desire to destroy.

If we can approach conversations with lower initial assumptions of malice, these conversations will go a lot better. Still, these conversations won’t be easy—it’s hard to resist the urge to clap back when someone compares your political position to the Nazis. But seeing someone as unintentionally offensive means their words hurt us less. And that’s a good step towards less outrage.

Great article guys. I think the effect of language and intention is something that can often be forgotten especially in this day and age where there can be a much stronger scrutiny on what is said versus the intention behind it, to a point where I think people are less encouraged (or perhaps less enthusiastic?) to explore the nuances of intentions.

I wrote about something similar here, which could arguably be a variation of the Protection Narrative (to use your framing) being pushed a little too far: https://curiositymindset.substack.com/p/now-less-than-ever

Thanks for your article!

Thanks for this. I really liked, and needed it. I wonder about one thing. Is there a difference between the intentions of the leaders (who directly profit from harming others) and the intentions of the voters (who are seeking Protection)?