Will Robots Tear Society Apart?

"Us Versus Them" and Machines

Several years ago, Jon Stewart, Barack Obama, and Jeff Bezos gathered at a White House Dinner and debated how automation might reshape the future of work. Bezos, the CEO of Amazon, sketched out a rosy future. He argued that his fulfillment centers were a model for collective harmony, where people worked together with robots to provide products for consumers. Stewart saw a darker future. He insisted that people wanted to feel proud of their work and that they were contributing to society, “not just running errands for people that have more than you.” Stewart concluded: “I think that's a recipe for revolution.” A hush fell over the crowd and then Obama piped up from the couch: 'I agree with Jon.'"

Utopic and Dystopic Crystal Balls

The disagreement between Bezos and Stewart illustrates the debate between those who believe automation/AI will create a utopia (the techno-optimists) and those who believe these tools will create a dystopia (the techno-pessimists). When Bezos and the techno-optimists gaze into their crystal balls, they see shining cities of economic growth and human happiness, as people seamlessly collaborate with our artificially intelligent friends. Despite some temporary hiccups (like workers losing their jobs to robots), we will all ultimately reap the benefits of efficiency: enhanced leisure time, freedom to pursue meaningful work, and a climate crisis averted.

The crystal balls of the dystopians show something much dimmer. The “rise of machines” will help the rich get richer and keep the poor down, magnifying inequality, unemployment, and causing a devastating climate catastrophe. Some reports suggest that up to 15% of the global workforce could see their jobs automated by 2030, causing massive economic and social instability. In this future, it isn’t hard to imagine those people deemed "undesirable” being hunted by machines whether the Terminator or the relentless robotic dogs of Fahrenheit 451.

Whether robots will save or destroy the world economy remains to be seen, but there is already evidence that automation and AI changes how we interact with each other. The rise of machines is powerfully shaping our psychology. The question is whether the rise of machines promises to bring humankind together or whether it will tear us apart…

Automation Might Tear Us Apart

There is no doubt that automation is capable of inciting social tensions, especially class tensions—the ones Jon Stewart emphasized. In 1811, in the middle of the Industrial Revolution, a group of highly skilled English artisans—”the Luddites”—conspired to meet under the cover of darkness to destroy sets of mechanized looms and weaving frames. These machines had slowly been putting these artisans out of business, and without governmental support, they turned to terrorism. They entered their own factories, wielding sledgehammers, guns, and righteous indignation.

Often, the protesting Luddites were met with bullets from the factory owners who were benefitting from these novel machines. Eventually, the government, sympathetic to the rich machine-owners, sent in 14,000 armed British soldiers to “quell” the protests. Many Luddites were shot, hanged, or exiled to Australia.

Today, in what Erik Brynjolfsson and Andy McAffee call the Second Machine Age, machines are driving us apart in new ways. There is a widespread perception that artificial intelligence and automation are driving unemployment in droves. Of course, these perceptions may not be true. Long-term trends suggest that automation drives (eventual) greater employment, and many economists see the advance of technology as a boon.

But threats are a matter of perception. People’s fears have a reality all of their own. And some recent work has shown that these fears about automation are dividing Americans. Regardless of recent news stories, America has long been exceptionally welcoming to immigrants (compared with other countries), but under conditions of scarcity, humans naturally tense up and draw sharper lines in the sand between us and them.

In 2020, Monica Jamez-Djokic and Adam Waytz published a social psychology article providing evidence for this claim. Their article showed how concerns about automation may incite hostility towards immigrants. In an experiment, they showed participants three scenarios: (1) that automation will likely (85%) eliminate the necessity for your job in a few years (2) that it is unlikely (4%) that your job will be automated in the next few years and (3) a control condition in which they read a report about general job losses. Participants who were merely exposed to information about automation financially discriminated against immigrants and supported more restrictive immigration policies. Nativist discrimination happened regardless of whether the prompt suggested automation had a high or low probability. In other words, just thinking about the rise of machines prompted anti-immigrant prejudice.

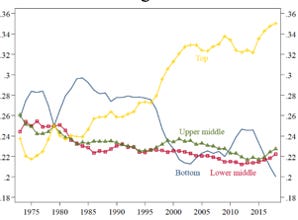

Concerns about automation clearly have some real-world connection with how people view immigrants. Many workers in “rust-belt” states—with jobs threatened by automation—seemed to embrace the anti-immigration policies of Donald Trump in the last two elections. Reams of articles, op-eds, and think pieces have been published about these disaffected “white working-class voters” and their concerns over globalization and immigration. Of course, immigration may not actually be threatening their jobs, but these folks are right about one thing: their labor has increasingly been devalued over time. In the age of increasing automation, wages have been steadily increasing for those at the top of the income distribution, while those in all other classes have been decreasing.

The rise of machines creates what economists call a “superstar economy” where the few people with non-automatable skills (and the ownership of machines) become increasingly valuable, while the automatable skills of most people become devalued. Regardless of whether you think this trend is fair when people feel like they are losing a zero-sum game, bad things start to happen. We look for people to blame, and we’re good at finding them, whether they are immigrants, people of a different ideology or religion, or elites. This blame leads to hate, and hate leads to violence, and violence to more violence. This is how automation might tear us apart.

The pressing question, then, is how to reap the benefits of automation without the social decay. Andrew Yang, amongst others, has proposed a Universal Basic Income (UBI) of $1,000 per month to all Americans. This solution is especially popular amongst people who believe automation will cause significant job displacement. David Graeber, in his book “Bullshit Jobs”, claims that our modern economy is overflowing with unnecessary and pointless jobs. Perhaps large portions of jobs should be automatized, and humans should be retrained and re-educated for different forms of work.

“The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations, of which the effects are perhaps always the same, or very nearly the same, has no occasion to exert his understanding”

- Adam Smith

Education could focus less on rote memorization and instead prioritize the cultivation of human skills (leadership, creativity, connecting ideas) that are less replaceable by machines. Others have gone in different directions, with Donald Trump advocating for nativist immigration and trade policy and Stephen Hawking claiming that some sort of world government may be needed to reign in the negative consequences of AI.

Automation Might Bring Us Together?

For every techno-pessimist worrying about class warfare, there is a techno-optimist seeing automation as a force for social connection. In the First Machine Age, cities flourished as people flocked to factories. This increased population density may have helped diseases spread, but it also accompanied sharp rises in interpersonal trust. As Durkheim argued, the increase in division of labor caused a feeling of “organic solidarity”, in which people depended on one another to complete tasks.

Now, in this Second Machine Age, techno-optimists argue that the digital revolution is connecting us more than ever before. AI fuels social media, which connects us to a diverse set of experiences around the globe, helping us to foster understanding across differences. The Center for the Science of Moral Understanding has published work showing how social connection might be fueled by the rise of robots—especially robots that look more human. Today, most robots look very mechanical (think Roombas and factory farms), but this is changing (see image below). Soon robots will look and talk like us.

In Season 2 Episode 1 (Be Right Back) of “Black Mirror,” series creator Charlie Brooker gives us a peek into what jaw-dropping roles a more realistic synthetic AI could fill in the future. Humanity will likely have to reckon between outlandish choices between a robot doctor and a human doctor, a robot lover or a human lover, or even a robot or a human workforce. While these kinds of thought experiments tend to provoke anxiety about robots, we have some evidence that these fears might be useful for bringing us together. Nothing unites humanity like a common enemy.

Across a series of studies, we found that the threat of a rising (and humanlike) robot workforce led people to see other people as more similar to themselves. It is true that people often have a hard time finding common ground with immigrants and people of different faiths, but it is easier to find similarities with other people than with robots. Immigrants may eat different food than you, but at least they eat food instead of relying on lithium batteries.

As an analogy for how robots can make people seem more similar, consider these two grids of squares laid side-by-side (Figure credit: Josh Jackson). We humans, are the red squares. When we look around at only other (red) humans, we see clear differences—burgundy is not pink, which is not fire-engine red. But once you realize that there is an entirely different color (blue!!), your perspective on red is broadened. Now you realize that these differences in shading are actually minor in the grand scheme of things. Without robots, it’s easy to see the differences in human beings, but when we all stand next to machines, our common humanity is obvious (we are all red!).

The perceptions of similarity caused by robots may help us reduce racial discrimination. In an experiment, our team (Led by Joshua Jackson) told participants to imagine themselves as the treasurer of a futuristic post-dystopian community where members each did some historical job (e.g., blacksmith, cook, etc...). They were instructed, as treasurer, to give bonuses to members of the hypothetical community based on what they saw as the most important jobs. Crucially, there were two conditions. One group of participants saw 30 pictures of community members, who varied in gender and race. Another group of participants saw 40 pictures: the same 30 pictures of community members + 10 additional robots who also performed these jobs. (Sample image below)

Participants who saw the 10 extra robot photos were more egalitarian (I.e., less racist or sexist) when assigning bonuses compared to those who saw only human community members. Who is Black and who is White matters less when you are wondering about who is made of flesh and who is made of silicon. In another study, we found that this increased equality was driven by “pan-humanism”—when people identify with all humankind. So, while it’s terrifying to be chased by the Terminator, at least it brings people together.

The Foes That Bind

You may have noticed something – we just presented two sets of findings arguing for two opposite outcomes: one about automation tearing us apart, and one about automation bringing us together. Which studies are right? We suggest both are correct, and that whether automation will unite or divide us might just depend on the framing.

Humans evolved to discriminate between us versus them. We form in-groups and out-groups naturally, but the exact identity of them is flexible. For thousands of years, Protestants and Catholics have seen one another as mortal enemies, but today Catholics and Protestants feel much more comfortable identifying as the same us: "Christians." That’s because they share a fear of a common them: Muslims and, especially, militant atheists. They have a common enemy. Common enemies don’t always eliminate group boundaries, but they function like a dial, making certain group boundaries more salient, and others less so.

Common enemies can bind people together but do so most effectively when they are other humans because our us versus them system is wired by evolution to form coalitions among human beings. Common threats that have united Americans include the rule of the British at the time of the American Revolution, the evil axes of World War I and World War II, the Russians of the Cold War, Osama bin Laden after 9/11, and now Putin in the war against Ukraine.

The times when common enemies fail to bring us together — and actually drive us apart — are the times when threats are not fellow human beings. Take climate change and the coronavirus. These are obvious threats to our survival—many more Americans have died from the coronavirus than from the Cold War or from 9/11, but the coronavirus is not another human being bent on the destruction of our way of life, releasing propaganda videos that insult our values. Instead, the coronavirus is just a virus. Because this kind of faceless threat doesn't trip our us versus them detector, we are left fighting against each other.

So here’s the real question — are robots a “them” in us versus them? Are they a common enemy or just a faceless threat that prompts us to attack each other? The answer depends on how human-like robots are. If the ranks of the rising robot workforce are filled with mechanical robots, they are unlikely to inspire humanity to rally together. It is hard to be filled with hate towards the Roombas that clean houses, or the orange box-like Kiva robots that move boxes around at Amazon fulfillment centers.

On the other hand, if you and your coworkers are all losing your jobs to robots that look and sound like other human beings, it’s much easier to band together against them in common hatred. Humanoid robots are humanlike enough to trigger our us versus them feelings, but not so much that they will be anything other than them. There is a reason why the movie Terminator features humanlike robots instead of a swarm of faceless drones. We can imagine a humanlike robot as a threat to our way of life and understand why that threat leads people to band together. On the other hand, it's hard to hate a collection of robotic arms, and so we end up just hating the people we compete with for jobs instead (or the wealthy people who own the robotic arms, if the Luddites are any indication).

No more robots?

At this point, perhaps you’re thinking, “I should toss my Roomba off a balcony?” Not quite. Robots are exceptionally useful. They eliminate mundane repetitive tasks and help us focus on work that feels truly human (creativity, expression, discernment). Robots hold so much promise and are so integrated into our society that demonizing them all will cause more problems than it will solve. We are also not advocating for the idea of making an army of humanoid robots so that workers of the world can unite in revolution against them.

Instead, we are advocating for more awareness. When scarcity or inequality looms, our minds go straight to human competitors — immigrants, people who don’t look, or people who don’t think like us — but in a modern world of complex systems, this blame is misplaced. Living together in a world of rising automation is not as easy as blaming immigrants, or the companies developing robots. Instead, we need thoughtful policy that both encourages the economic power of technology and respects people’s needs for work that not only covers the bills but also helps to provide a meaningful life.

Will the governments of the world be able to pass such forward-thinking policies? It’s unclear. What is clear, is that both the techno-optimists and the techno-pessimists are both right. Humanity has an opportunity to outsource more and more of the mundane to the realm of automation. We can exchange repetition for the parts of life that feel truly human. At the same time, there is a real risk that we don’t handle this transition well and fall deeper into political and class divisions. If movies are any guide, whether we become a utopia or dystopia hinges on a single hero who battles the rise of robots. But the movies are wrong. It’s up to each of us to make sense of who is part of us, and who is part of them—a question as old as humanity itself, but one that takes on a new urgency during the coming robot revolution.