Moms vs. Dads

Who’s Right in the Parental Blame Game?

Are dads doing more than ever, or are they as lazy as ever compared to their wives? The answer, it turns out, is both.

In this issue, we have a conversation with Dr. Corinne Low about her new book (Having It All: What Data Tells Us About Women’s Lives and Getting the Most Out of Yours), which explores the most intractable household conflicts: parental labor.

We write a lot about political conflicts, but the most personally upsetting moral conflicts often happen in the home with a partner. Were you a jerk to your in-laws, or did they push you too far? Was buying those clothes a justified treat for yourself, or was it a betrayal of your collective budget?

One of the most tenacious household conflicts revolves around the workload of Moms vs. Dads, with both parents feeling overworked and undervalued. This conflict has long been at the center of debates about feminism. Research finds that—even in couples initially committed to egalitarianism—women steadily take on more and more labor: “wifework.” This imbalance only increases when kids arrive.

For many, this conflict isn’t just an academic disagreement but an everyday battle. For me, it’s a disagreement between academics: One of us (Kurt) is a dad, and his partner has the exact same job (Professor Kristen Lindquist). When it comes to our two kids, we both feel overworked and underappreciated. But it’s clear that Kristen, as a mom, has the deck stacked against her.

Society views Kristen as more of the “default parent,” the one expected to text about playdates or remember to get the gift for the upcoming party. And this means that—unless we are very careful and explicit—the “parent work” often falls to her. But I also feel like I do a ton as a dad! How can both these realities be true?

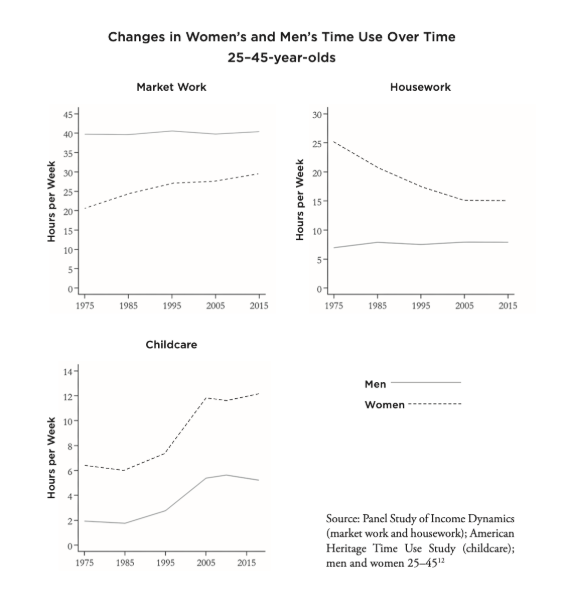

The data reveal how. Research shows that since 1975, fathers’ parenting time has increased drastically. This feels like a real win: men are way better dads than their own dads were. But they still do way less than moms.

Check out the graph below. Parenting time has increased massively for both men and women, but the gap between them has grown and is more pronounced than it was for the Baby Boomers. If you’re a dad, that’s a confusing narrative (“Wow, I drop my kids off every day; my dad never did that!”), and if you’re a mom, the growing load feels invisible (“I packed their lunches, washed their uniforms, and signed the permission slip...and all he did was drop them off.”).

It turns out that many moral disagreements revolve around these different perceptions: 1) perceptions of the same group over time (e.g., dads) vs 2) perceptions of one group versus another group (e.g., dads vs. moms).

That’s where Dr. Corinne Low comes in. She’s a behavioral economist and professor at Wharton, where she studies how couples divide labor, make decisions, and define fairness in everyday life. Her new book draws on personal stories and economic data to help women and couples navigate the pressures of modern family life.

We spoke with Dr. Low about the moral psychology of household labor—why exactly perceptions of fairness go awry, and how couples can move beyond blame into a shared understanding.

You write about how decisions are economic trade-offs—but they’re also moral judgments. Men often feel they’re being unfairly maligned as “bad partners” when the data show otherwise. How can couples move toward greater moral understanding of each other’s perspectives?

Well, I think that’s exactly where data can be helpful, and that’s why I encourage couples to track their time. Because it’s easy to get into a really loaded, emotional conversation about who does more and who is more exhausted. Data help ground the conversation in a more neutral, fact driven place. How much time are each of you spending, and on what tasks? How much leisure time is each partner getting, since this is a neutral metric of their contributions being valued equally as “work” within the relationship, even if they don’t earn the same.

Tensions over domestic load often come from not as much a disagreement about how the work should be shared, but disagreement about what the work actually is. That’s where invisible labor (one person ordering clothes and groceries and arranging playdates while at work) comes into play. It’s also where different expectations about domestic life matter—like one person valuing home-cooked food, and the other thinking takeout is fine.

So, for both partners: replace blame with curiosity. You’re starting from different places, shaped by different pressures—but progress comes when both partners extend compassion, stay open to change, and see the household as a shared project, not an arena for moral superiority. Winning the point is going to make you less happy in the long-run than investing in win-win solutions that meet both people’s needs.

You’ve noted that parenting time has gone up for men compared to the past, but even more for women, so the gap has actually widened. How do you recommend couples interpret these kinds of statistics without falling into “who has it worse” battles?

I think this is such a great opportunity to think about differing perspectives, and comparison points. Men are spending more time with children than in past generations, so compared to their dads, they feel like they’re doing a lot. But women’s time has increased even more, which actually widens the gap between genders. I think we can start by recognizing that modern family life is demanding more from everyone.

But then we need to also acknowledge that historical norms (and some biological realities, like breastfeeding) have left women starting from a higher baseline of responsibility in childcare. Partners should approach these numbers not as ammunition, but as context for conversation. Again, time tracking might highlight some revealing things about what this breakdown looks like in your household. And if both people value contributing equally, then it’s time to be practical in solving this problem. As I say in the book, you need to figure out how to divide tasks up at the root—so someone has complete responsibility for a whole task (e.g., not just packing lunch, but planning, shopping, packing, and emptying/ washing lunchboxes). Both people will be happier if you can play the roles of co-CEOs, rather than one manager and one junior employee!

What Low is describing is based on behavioral economics—but it’s also really about moral perception. Each partner is fixated on their concerns but isn’t able to see their partner’s. Differences in perspectives also drive disagreements about political issues (see our post on the assassination of a powerful CEO). In marriages and democracies, conflict starts from thinking that the “other side” isn’t seeing the “obvious truth” that you see.

What lessons do you think we can take from behavioral economics about how couples might reframe fairness so it’s not about tallying tasks but about shared understanding of the whole load?

Behavioral economics shows that our brains don’t measure effort or fairness very well. Cognitive phenomena like salience and mental accounting make us overestimate our own contributions and focus on visible, easy-to-count tasks while overlooking smaller, less obvious forms of work and mental load. Fairness in a household isn’t just about counting who did the dishes and picked up the kids; it’s about understanding the invisible cognitive burden and the overall system of work, and ensuring everyone is getting their needs met and has space to thrive as a full and complete human being. So instead of asking “Did we split the chores 50/50 this week?” it might be better to interrogate the balance of leisure, as I said, or more deeply, “Do we both feel supported, seen, and balanced in the whole of our responsibilities?”

If a couple wanted to start one conversation tonight that would build both data-driven fairness and moral empathy, what would you suggest they talk about?

I think the start of the conversation can be: “What does a fair partnership feel like to you?” Each partner can lay out what they see as the actual distribution of tasks, both visible and invisible, and these facts about social norms and historical legacies of labor can enter the conversation. It also invites moral empathy—each partner can describe what feels supportive or unsustainable, and why.

But from that start, I really feel like you need data to continue the conversation well! You both might be surprised by how reality aligns with that expectation, and how much labor is going unrecognized. But, because you’ve established the baseline normative view before getting into the empirical reality, you now have that to refer back to in trying to make adjustments!

Don’t try to change everything at once. Once you have your data, ask, “What small step can we take now that will make our empirical reality closer to our normative vision?”

Dr. Low suggests focusing on sharing your perspective—how you feel about the workload divide—and harnessing data to present it to your partner to start to create a more equal balance (first personal experiences, then the facts). And as anyone who’s ever been critiqued can tell you—this takes a healthy amount of moral humility.

And the data don’t lie: even as fathers are doing more than ever, the total load on mothers has grown even faster. When each person is measuring from their own reference point (“Compared to my dad, I’m doing a ton”), you can end up talking past each other.

But understanding is possible, if you’re able to listen to your partner and appreciate their perspective (and their reference point). But appreciation isn’t enough—you have to then try to do something concrete to bridge the gap.

Of course, like many divides, the gap between moms and dads is hard to fully address, but knowing the data is a good start. Thanks for reading—now I’m off to text the neighborhood dads about playdates.

Corinne Low is an associate professor of business economics and public policy at the Wharton School. Her new book Having It All: What Data Tells Us About Women’s Lives and Getting the Most Out of Yours is available wherever books are sold.

This is so great, thank you so much for sharing this convo!!

When both paid and unpaid work hours are added, aren’t men actually working slightly more total hours?